The year was 1970, and America was chaos.

The country was fractiously polarized along every line – age, race, religion, politics. The world still reeled from the assassinations of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr. A troop of National Guard soldiers opened fire on an unarmed group of college students. “Vietnam” was a hot-button word wherever you went.

It was, to put it gently, an insane time for America, perhaps its bitterest and most contentious stretch in modern history. (And that’s saying a lot, given… y’know, nowadays.) Between the mutual distrust and the violent protests, the late ‘60s and early ‘70s defined political and social turbulence for the generation of young Americans who would someday become the recipient of endless “Ok Boomer” memes.

In difficult times, pop-culture tends to lean into escapism. So it was that the top-rated TV show of the 1969 fall season was the hilarious Laugh-In, closely followed by old Western reliables Gunsmoke and Bonanza. 1969’s highest-grossing film, by a wide margin, was also a Western (Butch Cassidy & the Sundance Kid), and the Beatles topped the record charts with The White Album and Abbey Road.

There was at least one mode of pop-culture that, as a new decade of anger and uncertainty dawned, had begun taking on the world’s problems a little more seriously and directly – the four-color, multi-paneled medium known as the comic book.

For much of the 1960s, comics had leaned heavily on escapism – Superman battled aliens, Batman took on sea monsters, and Wonder Woman fought a talking Chinese egg with a prehensile mustache. (Don’t ask.) But as the new decade approached, some comic book writers began injecting more serious, real-world sensibilities into their stories.

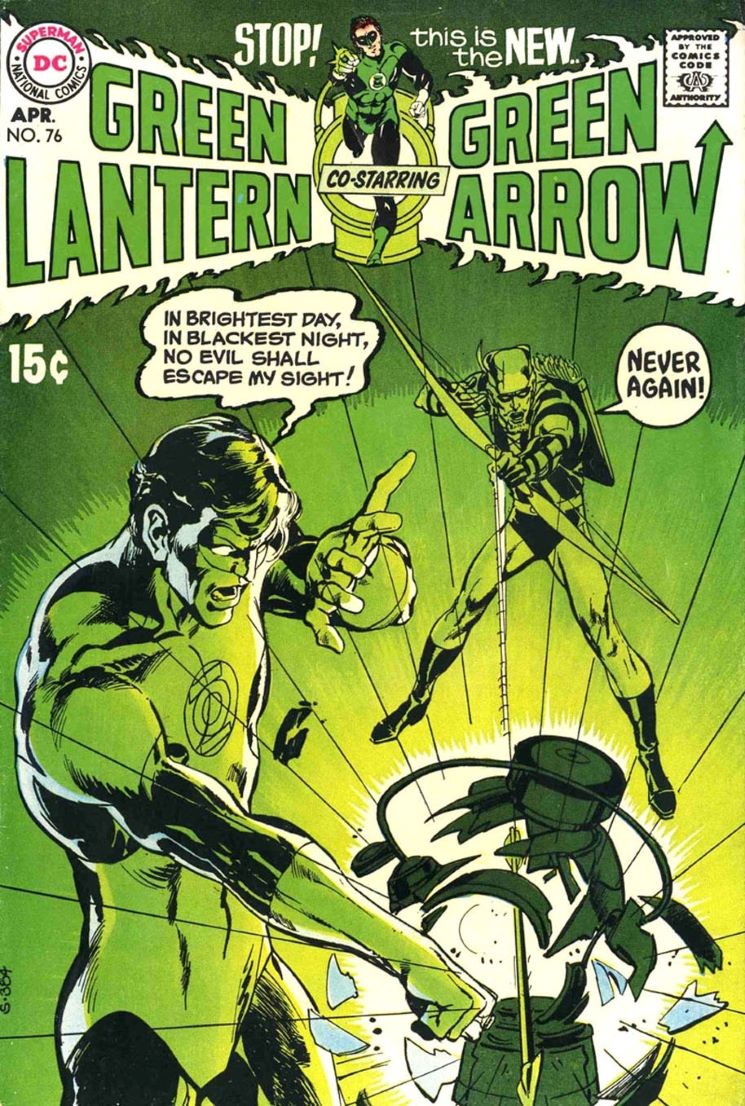

Marvel led the way with storylines geared toward the college-age set – Spider-Man dealt with campus protestors, the X-Men frequently drew parallels to the Civil Rights movement. Sensing potential in the well of social commentary, DC decided to take it to a further extreme. And thus, in April 1970, the world was introduced to one of the most overtly political series in comic book history: Green Lantern/Green Arrow.

Despite their similar taste in color choice (shared by Goblin, Hornet, and some guy called Lama), Green Lantern and Green Arrow didn’t have much direct connection before the ‘70s. Both characters had been introduced in the early 1940s with very different skill sets (Lantern, aka Alan Scott, fought crime with the aid of a magic ring; Arrow, alias Oliver Queen, was initially a poor man’s cross between Batman and Robin Hood), and both varied in popularity. Lantern earned his own comic book pretty quickly, while Arrow was stuck as a backup feature in other comics for over 20 years.

By the early ‘60s, the escapist tone of comics had allowed both of DC’s verdant vigilantes to thrive more freely. A new Green Lantern was introduced, bearing the name Hal Jordan, and quickly grew into one of DC’s most popular heroes. Arrow’s ongoing adventures ended in 1964, but he and Jordan continued as players in one of DC’s most popular titles – Justice League of America.

Then in 1968, Justice League scribe Gardner Fox exited DC Comics, to be replaced by the young (and, as was crucial in those days, hip) Denny O’Neil. Though O’Neil’s early JLA stories continued the escapist sensibilities of Fox’s tenure, his penchant for social commentary soon began to shine.

Under O‘Neil’s pen, the League battled an alien villain trying to destroy the world through pollution. (They eventually defeated him when he was forced to breathe clean air.) They also faced a seemingly ordinary bad guy who energized large crowds by stirring their fears about immigrants and minorities. (At one point, the villain imprisons Batman in something called “the Trump satellite.” Why hasn’t Twitter been all over this?) The stories weren’t exactly subtle in their messaging, but their bold attempts to tackle politics head-on made them stand out in the increasingly competitive market.

Recognizing O’Neil’s potential, DC put him on the Green Lantern series, which had seen its sales decline by 1970. He was partnered with artist Neal Adams, another young recruit who had already gained recognition for his Batman stories in The Brave and the Bold. Along with writer Bob Haney, Adams had helped envision a new and grittier Batman, one far removed from the goofy and widely recognizable Adam West series. This Batman fought not only criminals and supervillains but Gotham City corruption, helped by unconventional heroes like Deadman and the Creeper.

One of these Brave & Bold stories also introduced a more serious version of Green Arrow. The millionaire Oliver Queen loses his fortune and grows a Van Dyke beard – unclear if the former event sparks the latter – and becomes a “hero on the street,” championing left-wing politics as he combats wealthy corporate fat cats in defense of the poor and downtrodden. (We could probably talk about how Oliver doesn’t start criticizing the one-percent until the moment he no longer counts himself among them, but that’s an essay for another time.)

Adams’ tenure on Brave & Bold lasted only eight issues, as he was quickly promoted to the main Batman book, where he and O’Neil began one of the most memorable chapters in the Dark Knight’s history. The Batman work is what the O’Neil/Adams duo are best known for, but we’re here to talk about their less-recognized collaborative work on Green Lantern/Green Arrow. (And about time, too – we’re almost a thousand words into this sucker.)

The story kicked off in Green Lantern #76, titled “No Evil Shall Escape My Sight!” It began innocently enough, with Lantern rescuing an unarmed man from a group of apparent thugs. But wait! As Green Arrow points out, the “helpless man” is actually a powerful landlord, taking advantage of the black and brown families stuck in his tenements, and his penny-pinching cruelty has made his tenants furious. Oliver accuses Hal of playing judge and jury, using a very cut-and-dried sense of right and wrong in a morally grey world.

The new direction of the Green Lantern series is exemplified in a key scene where one of the tenants, an elderly African-American man, confronts GL directly. “I been readin’ about you,” the man says. “How you work for the blue skins… and how on a planet someplace you helped out the orange skins… and you done considerable for the purple skins! Only there’s skins you never bothered with – the black skins! I want to know… how come? Answer me that, Mr. Green Lantern!”

In response, Hal only hangs his head in shame: “I… can’t…”

This little three-panel exchange exemplifies both the strengths and weaknesses of the ensuing Green Lantern/Green Arrow run. It gets across a key point that juxtaposes science fantasy with cold, brutal reality… but it does so in a manner that doesn’t feel the least bit subtle.

This sets the tone for the next twelve issues of Green Lantern, which see Lantern and Arrow, occasionally joined by Black Canary (then Ollie’s on-and-off paramour), embarking on a “journey across America,” dealing with topics like racism, immigration, drugs, and the environment. These were issues not normally touched on by any comics of the day, which gave the series a unique flavor to its own. But the series’ ham-handedness was a problem then, and is even more noticeable nowadays, especially when the stories are read in swift succession. (Binge-reading! It’s all the rage during quarantine.)

Take, for instance, the second Lantern/Arrow story, “Journey to Desolation!” The tale sees Hal and Ollie travelling to a worn-out little valley town quite literally named Desolation, its population overtaken and exploited for mining work by a shady grifter named Slapper Soames. A villain whose dialogue and demeanor are as cartoonish as his name, Soames keeps the townsfolk under a brutal thumb, imprisoning and killing any dissenters. To drive home his role as the villain of the story, Soames is saddled with a group of Nazi henchmen – and I don’t mean the “basement-dwelling online troll Nazis,” I mean the literal “worked for the Third Reich in the ‘40s and are now third-rate comedy henchmen” Nazis.

The story also calcifies several tropes of the brief series, such as Green Lantern’s unwillingness to question authority, and Green Arrow convincing him otherwise by giving a long speech that compares the villain to Hitler. (Kind of already underscored by the Nazi henchmen thing, but Ollie is never one to let a Hitler comparison go to waste.) The story had a heavy topic on its mind, but dealt with it in a quick, choppy way, with a one-note villain and an ethical quandary that is resolved almost before it’s even brought up.

Over the next several stories, Lantern and Arrow stumbled across every social issue plaguing early ‘70s America – an “enlightened” cult of racist murderers; a town overrun by a lying, manipulative media machine; a planet plagued by overpopulation; an industrial complex which spreads pollutants into the atmosphere. Each of these stories followed a familiar pattern – comically exaggerated villain that no one could take seriously, and Arrow lecturing a reluctant Lantern about the importance of intervening, and an ending which suggested that the True Problem had not been resolved. There was also heavy-handed symbolism – a nomadic environmentalist is depicted in the pollution story as being a Christ-like figure, to the point that a raging mob ties him, cross-like, to a plane propeller – and fairly retrograde depictions of characters who weren’t white men. (O’Neil has had a long history of writing women poorly – after years of Gardner Fox writing Wonder Woman as just another superhero, O’Neil’s very first Justice League featured her donning an apron and ordering her fellow superheroes to start cleaning up the League’s headquarters. That’s just one example on a very long list, folks; don’t get me started.)

The best story in the GL/GA run is “Snowbirds Don’t Fly!”, the opening of a two-issue arc that tackles drugs and substance abuse among America’s youth. Marvel Comics had led the way weeks earlier with a three-issue Spider-Man storyline that dealt with Harry Osborn’s drug addiction (a story so controversial that it wound up being published without the seal of approval from the Comics Code Authority), but DC gave a darker and more intriguing take on the subject, showing the effects of heroin in more discomforting detail and revealing that Green Arrow’s onetime sidekick, Speedy (aka Roy Harper), had become a user. As with many other books in the series, “Snowbirds” wasn’t subtle and fell back on the trope of a powerful villain profiting off the addictions of the downtrodden, but it developed its story well over two issues and featured an unexpectedly raw characterization of the Oliver/Roy relationship, focusing on how neglectful the man has been to his loyal ally. (It’s also refreshing, for once, to have Ollie be the recipient of the lecture, rather than the ones who sermonizes others.) The story was so popular that it was worked into the CW’s Arrow TV series decades later.

The other significant development of the run was the introduction of John Stewart, a new Green Lantern who would make his mark as DC’s first African-American superhero. (Marvel had laid the groundwork with Black Panther in 1968.) The story portrays John as a hot-tempered ghetto resident who clashes with cops and quickly clashes with Hal as well. When a racist Presidential candidate (presumably inspired by George Wallace) is marked as an assassin’s target, the two Lanterns don’t see eye-to-eye on the issue of protecting him. I won’t spoil the story’s incredibly contrived ending, but I will award no prizes if you guess that it ends with Hal learning a valuable lesson.

Look, before you start sniping at me in the comments, let me clear things: I don’t hate this series. I think it’s flawed, to be sure, but it’s still an impressive accomplishment, and a bold step in moving comic books beyond the “kid stuff” label they were given in their first few decades. And Neal Adams’ artwork remains a knockout, even five decades later. Perhaps most importantly, while the storytelling and dialogue haven’t aged very well, several of its messages are just as resonant in 2020 as they were in 1970. (And yes, that is something for which you can snipe at me in the comments.)

Ultimately, Green Lantern/Green Arrow was a commercial failure, and GL’s book was cancelled in 1972 with issue #89. Hal became a backup feature in The Flash, with stories (still written by O’Neil, though drawn by a variety of non-Adams artists) that veered more toward conventional sci-fi; Green Arrow moved to less politically-themed storylines in Action Comics. Both would eventually regain their own titles, and have battled for verdant dominance on the DC shelves to this day.

But their brief alliance in the early 1970s, for all its faults, remains a crucial historical footnote. It’s an effective time capsule to a tough and turbulent era, when a generation of Americans learned to tough it out and return things to relative stability. And therein lies the ultimate lesson for our own crazy times: They worked through it, and so can we. Ok Millennial?

One thought on “Fifty Years Later: How Green Lantern and Green Arrow Changed Comics Forever”